Many (but not all) the magazines listed below are available on Archive.org and have no restrictions. The publisher Christian History Institute is a non-profit organization and I highly recommend subscribing to Christian History Magazine for their edifying and inspiring articles. Click here for more information. The titles below are accompanied by a short excerpt but if a topic interests you, I would strongly recommend reading the entire issue for that topic. You will definitely learn something about the topic you did not know. The articles are replete with many excellent illustrations and pictures.

100 Most Important Events in Church History - Christian History Magazine #28

Welcome to This Special Issue - Important information before you begin. This issue is a first for CHRISTIAN History. For twenty-seven issues, we have focused on particular individuals, movements, or events. But never have we stepped back to look at the broad, two thousand-year sweep of Christian history. We have looked at individual trees— grand oaks such as Augustine and Calvin—but not the forest.

The very idea seemed overwhelming. How could we possibly present an overview of church history in one issue? Latourette’s classic A History of Christianity requires 1,552 pages of fine print to accomplish the same.

Yet readers had asked for an issue that would orient them to church history, an introductory guide that might be used in classes or discussion groups. And we wanted to show how the diverse figures covered in previous issues of CuristiAN History—Bernard of Clairvaux, John Wesley, and C. S. Lewis, to name three—fit into the sweep of history. By understanding each person’s context, we can better understand his or her contribution.

I discussed these ideas with Christian History's founder, Dr. Ken Curtis, and he mentioned a book he was planning: The 100 Most Important Events in Church History. The idea made sense for the magazine, too. Perhaps we couldn’t draw a detailed map for every mile of the church’s journey, but we could sketch the most significant landmarks, milestones, and turns in the road. The Council of Nicea, Luther's posting of The Ninety-Five Theses, John and

Charles Wesley's conversions—these events clearly changed the course of church history. In highlighting these key events, we hoped, we could help people see the big picture, the development and change of the Christian church over time. The project would be an adventure, but we felt it was worth the risk.

How were the events selected? Selecting only one hundred key events from church history is not easy. We felt as if we had been given only an afternoon to tour the Louvre, probably the finest collection of paintings in the world. Where do you start, when the museum holds works by Vermeer, Rubens, El Greco, Raphael, and Titian?

Still, a qualified tour guide could show you what are generally considered the more significant works: Rembrandt’s The Supper at Emmaus, or Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa. This issue of Christian History aims to be a similar guide through a history filled with treasures.

To determine the dates deserving coverage, extensive research was done by the Christian History Institute and by Christianity Today, Inc. First, a survey was sent to members of the Christian History Institute. Responses were tabulated, the list of events was refined, and a new survey was written.

This was sent to five hundred members of a professional church historians’ society. The group represented a dazzling array of denominations, theological positions, and areas of historical study. Seventy-one percent of respondents hold doctoral degrees.

The survey listed nearly 150 events in church history— the Diet of Worms, the Second Vatican Council, and so on—and asked respondents to mark whether each event was “extremely important,” “very important,” ‘‘somewhat important,” “not too important” (or “not familiar’ to them). The survey also invited respondents to suggest other church-history dates they considered extremely important.

Finally, the survey was sent to the editorial advisory board of CuristiAN History. These historians completed the survey and suggested still other events worthy of inclusion.

Survey results were tabulated, and “write-in’’ events were thoughtfully compared and evaluated. From this information, a list of the 100 most important events in church history was compiled. (And from that, a list of the 25 most important dates.)

We found the list interesting, educational—and at least in a few places, surprising.

The Most Important Events in Church History (SEE FULL COLOR TIMELINE OF IMPORTANT EVENTS)

- Titus Destroys Jerusalem

- The “Edict of Milan’

- The First Council of Nicea

- Athanasius Defines the New Testament Canon Augustine Converts to Christianity

- Augustine Converts to Christianity

- Jerome Completes the Vulgate

- The Council of Chalcedon

- Benedict Writes His Monastic Rule

- Vladimir Adopts Christianity/“Christianization of Russia”

- The East-West Schism

- Pope Urban II Launches the First Crusade

- Thomas Aquinas Concludes Work on Summa Theologiae

- The Great Papal Schism

- Gutenberg Produces the First Printed Bible

- Luther Posts the Ninety-five Theses

- The Diet of Worms

- The Anabaptist Movement Begins

- The Act of Supremacy

- Calvin Publishes Institutes of the Christian Religion

- The Council of Trent Begins

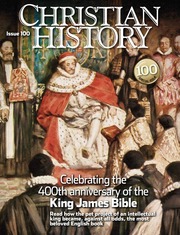

- Publication of the King James Bible

- John and Charles Wesley Experience Conversions (THIS IS FASCINATING READING)

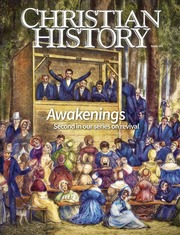

- The Great Awakening

- The Second Vatican Council

- Martin Luther King, Jr., Leads the March on Washington.

Christian History Magazine #1 - Zinzendorf and the Moravians

A Prayer Meeting that Lasted 100 Years by LESLIE K. TARR

FACT: The Moravian Community of Herrnhut in Saxony, in 1727, commenced a round-the-clock “prayer watch” that continued nonstop for over a hundred years.

FACT: By 1791, 65 years after commencement of that prayer vigil, the small Moravian community had sent 300 missionaries to the ends of the earth.

Could it be that there is some relationship between those two facts? Is fervent intercession a basic component in world evangelization? The answer to both questions is surely an unqualified “yes.”

That heroic eighteenth-century evangelization thrust of the Moravians has not received the attention it deserves. But even less heralded than their missionary exploits is that hundred-year prayer meeting that sustained the fires of evangelism.

During its first five years of existence the Herrnhut settlement showed few signs of spiritual power. By the beginning of 1727 the community of about three hundred people was wracked by dissension and bickering. An unlikely site for revival!

Zinzendorf and others, however, covenanted to prayer and labor for revival. On May 12 revival came. Christians were aglow with new life and power, dissension vanished and unbelievers were converted.

Looking back to that day and the four glorious months that followed, Zinzendorf later recalled: “The whole place represented truly a visible habitation of God among men.”

A spirit of prayer was immediately evident in the fellowship and continued throughout that “golden summer of 1727,” as the Moravians came to designate the period. On August 27 of that year twenty-four men and twenty-four women covenanted to spend one hour each day in scheduled prayer.

Some others enlisted in the “hourly intercession.”

“For over a hundred years the members of the Moravian Church all shared in the ‘hourly intercession.’ At home and abroad, on land and sea, this prayer watch ascended unceasingly to the Lord,” stated historian A. J. Lewis.

The Memorial Days of the Renewed Church of the Brethren, published in 1822, ninety-five years after the decision to initiate the prayer watch, quaintly describes the move in one sentence: “The thought struck some brethren and sisters that it might be well to set apart certain hours for the purpose of prayer, at which seasons all might be reminded of its excellency and be induced by the promises annexed to fervent, persevering prayer to pour out their hearts before the Lord.”

The journal further cites Old Testament typology as warrant for the prayer watch: “The sacred fire was never permitted to go out on the altar (Leviticus 6:13); so in a congregation is a temple of the living God, wherein he has his altar and fire, the intercession of his saints should incessantly rise up to him.”

That prayer watch was instituted by a community of believers whose average age was probably about thirty. Zinzendorf himself was twenty-seven.

The prayer vigil by Zinzendorf and the Moravian community sensitized them to attempt the unheard-of mission to reach others for Christ. Six months after the beginning of the prayer watch the count suggested to his fellow Moravians the challenge of a bold evangelism aimed at the West Indies, Greenland, Turkey and Lapland. Some were skeptical, but Zinzendorf persisted. Twenty-six Moravians stepped forward the next day to volunteer for world missions wherever the Lord led.

The exploits that followed are surely to be numbered among the high moments of Christian history. Nothing daunted Zinzendorf or his fellow heralds of Jesus Christ—prison, shipwreck, persecution, ridicule, plague, abject poverty, threats of death. His hymn reflected his conviction:Ambassador of Christ,

Know ye the way ye go?

It leads into the jaws of death,

Is strewn with thorns and woe.Church historians look to the eighteenth century and marvel at the Great Awakening in England and America which swept hundreds of thousands into God’s Kingdom. John Wesley figured largely in that mighty movement and much attention has centered on him. It is not possible that we have overlooked the place which that round-the-clock prayer watch had in reaching Wesley and, through him and his associates, in altering the course of history?

One wonders what would flow from a commitment on the part of twentieth-century Christians to institute a “prayer watch” for world evangelization, specifically to reach those, in Zinzendorf’s words, “for whom no one cared.”

Christian History Magazine #3 - John Wycliffe

John Wycliffe trained “poor preachers” who lived a simple life and traveled around the countryside teaching the Word of God to the common folk of England in their own tongue.

John Wycliffe was responsible for the very first translation of the entire Bible into the English language. John Wycliffe is called “the father of English prose” because the clarity and the popularity of his writings and his sermons in the Middle English dialect did much to shape our language today.

One of Shakespeare’s greatest comic characters, Sir John Falstaff, was based on an English knight who was a follower of Wycliffe and who died a martyr’s death.

One Pope issued five bulls against John Wycliffe for heresy, the Catholic Church in England tried him three times, and two Popes summoned him to Rome, but Wycliffe was never imprisoned nor ever went to Rome.

Although his English followers, called Lollards or Wycliffites, were persecuted and practically disappeared from England, John Wycliffe’s influence on the Bohemians influenced the great Protestant Reformation of the early 16th Century.

In the 14th Century world, Oxford was Europe’s most outstanding university and John Wycliffe was its leading theologian and philosopher.

John Wycliffe’s patron and protector, John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, was also the patron of Geoffrey Chaucer and both the preacher and the poet worked in the duke’s services at one time in their lives.

The writings of John Hus, the Bohemian reformer, which got him condemned and burned at the stake, depended heavily on translations and adaptations of tracts, treatises, and sermons by John Wycliffe.

The Wycliffe translation of the Bible was made from a Latin language, hand-written manuscript of a translation a thousand years old and before any verse numbers had been assigned.

With all of his questioning of the doctrines of the church and his criticism of the corruption of the clergy, John Wycliffe was never excommunicated nor did he ever leave the church, but, in fact, he suffered his fatal stroke while at Mass.

Even though John Wycliffe died peacefully at home in bed on New Year’s Eve, the Church exhumed his body 44 years later, burned his bones, and scattered the ashes in a nearby river.

At the Diet of Worms in 1521, Martin Luther was accused of renewing the errors of Wycliffe and Hus by making the Scriptures his final authority.

Christian History Magazine #4 Zwingli -

Christian History Magazine #8 Jonathan Edwards and the Great Awakening

Christian History Magazine #14 Money in Christian History

Christian History Magazine #22 Waldensians: Ancient “Evangelicals” from the Italian Alps

Christian History Magazine #40 The Crusades

Christian History Magazine #41 The American Puritans

Christian History Magazine #43 How We Got Our Bible

Christian History Magazine #46 John Knox: The Thundering Scot

Christian History Magazine #52 Hudson Taylor & Missions to China

Christian History Magazine #53 William Wilberforce and the Century of Reform

Christian History Magazine #81 John Newton: Author of “Amazing Grace”

Christian History Magazine #29 - C. H. Spurgeon (See also C.H.Spurgeon's Testimony)

Did You Know? ERIC W. HAYDEN A collection of true and unusual facts about Charles Haddon Spurgeon

Charles Haddon Spurgeon is history’s most widely read preacher (apart from the biblical ones). Today, there is available more material written by Spurgeon than by any other Christian author, living or dead.

One woman was converted through reading a single page of one of Spurgeon’s sermons wrapped around some butter she had bought.

Spurgeon read The Pilgrim’s Progress at age 6 and went on to read it over 100 times.

The New Park Street Pulpit and The Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit—the collected sermons of Spurgeon during his ministry with that congregation—fill 63 volumes. The sermons’ 20-25 million words are equivalent to the 27 volumes of the ninth edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica. The series stands as the largest set of books by a single author in the history of Christianity.

Spurgeon’s mother had 17 children, nine of whom died in infancy.

When Charles Spurgeon was only 10 years old, a visiting missionary, Richard Knill, said that the young Spurgeon would one day preach the gospel to thousands and would preach in Rowland Hill’s chapel, the largest Dissenting church in London. His words were fulfilled.

Spurgeon missed being admitted to college because a servant girl inadvertently showed him into a different room than that of the principal who was waiting to interview him. (Later, he determined not to reapply for admission when he believed God spoke to him, ‘‘Seekest thou great things for thyself? Seek them not!”)

Spurgeon’s personal library contained 12,000 volumes—1,000 printed before 1700. (The library, 5,103 volumes at the time of its auction, is now housed at William Jewell College in Liberty, Missouri.)

Before he was 20, Spurgeon had preached over 600 times.

Spurgeon drew to his services Prime Minister W. E. Gladstone, members of the royal family, Members of Parliament, as well as author John Ruskin, Florence Nightingale, and General James Garfield, later president of the United States.

The New Park Street Church invited Spurgeon to come for a 6-month trial & period, but Spurgeon asked to come ¥’ for only 3 months because “the congregation might not want me, and I do not ‘wish to be a hindrance.”

A caricature of Spurgeon (shown preaching in the Metropolitan Tabernacle’s “crow’s nest’’) from the December 10, 1870, edition of Vanity Fair. The " drawing was number 16 in the magazine’s “Men of the Day” series. The accompanying text described Spurgeon as “honest, resolute, and sincere; lively, entertaining, and, when he pleases, jocose.””

When Spurgeon arrived at The New Park Street Church, in 1854, the congregation had 232 members. By the end of his pastorate, 38 years later, that number had increased to 5,311. (Altogether, 14,460 people were added to the church during Spurgeon’s tenure.) The church was the largest independent congregation in the world.

Spurgeon typically read 6 books per week and could remember what he had read—and where—even years later.

Spurgeon once addressed an audience of 23,654—without a microphone or any mechanical amplification.

Spurgeon began a pastors’ college that trained nearly 900 students during his lifetime—and it continues today.

In 1865, Spurgeon’s sermons sold 25,000 copies every week. They were translated into more than 20 languages.

At least 3 of Spurgeon’s works (including the multi-volume Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit series) have sold more than 1,000,000 copies. One of these, All of Grace, was the first book ever published by Moody Press (formerly the Bible Institute Colportage Association) and is still its all-time bestseller.

During his lifetime, Spurgeon is estimated to have preached to 10,000,000 people.

Spurgeon once said he counted 8 sets of thoughts that passed through his mind at the same time while he was preaching.

Testing the acoustics in the vast Agricultural Hall, Spurgeon shouted, ‘’Behold the Lamb of God which taketh away the sin of the world.” A worker high in the rafters of the building heard this and became converted to Christ as a result.

Susannah Thompson, Spurgeon’s wife, became an invalid at age 33 and could seldom attend her husband’s services after that.

Spurgeon spent 20 years studying the Book of Psalms and writing his commentary on them, The Treasury of David.

Spurgeon insisted that his congregation’s new building, The Metropolitan Tabernacle, employ Greek architecture because the New Testament was written in Greek. This one decision has greatly influenced subsequent church architecture throughout the world.

The theme for Spurgeon’s Sunday morning sermon was usually not chosen until Saturday night.

For an average sermon, Spurgeon took no more than one page of notes into the pulpit, yet he spoke at a rate of 140 words per minute for 40 minutes.

The only time that Spurgeon wore clerical garb was when he visited Geneva and preached in Calvin's pulpit.

By accepting some of his many invitations to speak, Spurgeon often preached 10 times in a week.

Spurgeon met often with Hudson Taylor, the well-known missionary to China, and with George Miller, the orphanage founder.

Spurgeon had two children—twin sons—and both became preachers. Thomas succeeded his father as pastor of the Tabernacle, and Charles, Jr., took charge of the orphanage his father had founded.

Spurgeon’s wife, Susannah, called him Tirshatha (a title used of the Judean governor under the Persian empire), meaning “Your Excellency.”

Spurgeon often worked 18 hours a day. Famous explorer and missionary David Livingstone once asked him, “How do you manage to do two men’s work in a single day?” Spurgeon replied, ‘You have forgotten that there are two of us.”

Spurgeon spoke out so strongly against slavery that American publishers of his sermons began deleting his remarks on the subject.

Occasionally Spurgeon asked members of his congregation not to attend the next Sunday’s service, so that newcomers might find a seat. During one 1879 service, the regular congregation left so that newcomers waiting outside might get in; the building immediately filled again.

Eric W. Hayden, formerly minister at the Metropolitan Tabernacle, is the author of numerous books on Spurgeon, including Searchlight on Spurgeon (Pilgrim, 1973).

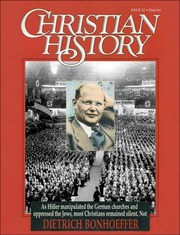

Christian History Magazine #32 - Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was a twin. (He was born just before his twin sister, Sabine.Dietrich’s father, Karl, was Berlin’s leading psychiatrist and neurologist from 1912 until his death in 1948. Dietrich was so skilled at playing the piano that fora time he and his parents thought he might become a professional musician. At 14, Bonhoeffer announced matter-of-factly that he was going to become a theologian. Bonhoeffer earned his doctorate in theology when he was only 21. Though later he was an outspoken advocate of pacifism, Bonhoeffer was an enthusiastic fan of bullfighting. He developed the passion while serving as assistant pastor of a German-speaking congregation in Barcelona, Spain. Bonhoeffer was ordained, church seminaries were complaining that over half the candidates for ordination were followers of Hitler. In 1933, when the government instigated a one-day boycott of Jewish owned businesses, Bonhoeffer’s grandmother broke through a cordon of SS officers to buy strawberries from a Jewish store. In his short lifetime, Bonhoeffer traveled widely. He visited Cuba, Mexico, Italy, Libya, Denmark, and Sweden, among other countries, and he lived for a time in Spain, in England, and in the United States. Bonhoeffer taught a confirmation class in what he described as “about the worst area of Berlin,” yet he moved into that neighborhood so he could spend more time with the boys. Bonhoeffer was fascinated by Gandhi's methods of nonviolent resistance. He asked for—and received—permission to visit Gandhi and live at his ashram. The two never met, however, because the crisis in Germany demanded Bonhoeffer’s attention. © Bonhoeffer served as a member of the Abwehr, the military-intelligence organization under Hitler. (He was actually a double agent. While ostensibly working for the Abwehr, Bonhoeffer helped to smuggle Jews into Switzerland—and do other underground tasks.) Bonhoeffer studied for a year in New York City. He was uniformly disappointed with the preaching he heard there: “One may hear sermons in New York upon almost any subject; one only is never handled, . . . namely, the gospel of Jesus Christ, of the cross, of sin and forgiveness. . . .”

How the Church in China Survived and Thrived in the 20th Century #98

Published to coincide with the 2008 Beijing Olympics, this edition of Christian History magazine examines the rise of the Christian faith in China during the 20th and early 21st centuries.

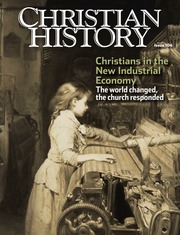

Christian History Magazine #104: New Industrial Economy

How did the church respond to widespread changes brought on by the Industrial Revolution? Jobs being lost to machines. Instant communication across continents. A widening gap between rich and poor. Sounds like the 21st Century? Certainly. But these realities first hit the scene with the dawning of the Industrial Age over 150 years ago. How did the church respond as this new world emerged, and what can we learn from the success and failures of our predecessors? Find out in this thought-provoking, thoroughly relevant issue of Christian History magazine.

THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION REPLACED HUMAN SKILLS WITH MACHINE SKILLS ALL OVER EUROPE AND AMERICA

HOW THE OTHER HALF LIVED Workers who moved to the cities often ended up in cheap, crowded, unsanitary tenements such as this on Baxter Street, New York City.

RISE OF THE MACHINES

PREVIOUSLY, INDUSTRIES “put out” jobs to workers, giving them raw materials and coming around to collect the results. Industrialization centralized this whole process. According to one history, the number of handloom weavers in Lancashire dropped from 240,000 in 1820 to only 188,000 by 1835. Their wages decreased from more than three shillings to just over two for a piece of calico. By 1861 only 7,000 hand weavers remained. The number of powerlooms increased from 2,400 to 400,000 in the same time period.

CENTRALIZING WORK meant centralizing workers. London grew from housing one-fifth of Britain’s population in 1800 to half the population by 1850. In New York City, population doubled every decade from 1800 to 1880.

TODAY THE WORD “LUDDITE?” describes someone who opposes advances in computing technology. Two hundred years ago, it was used for textile workers who smashed machines that were displacing them. The movement began with a series of disturbances in 1811 in northern England. Luddites took their name from the apocryphal figure Ned Ludd, who had supposedly broken a knitting frame after a superior admonished him.

BEER AND BIBLES?

ARTHUR GUINNESS (see “Godless capitalists?” pp. 33-36) not only produced a line of brewers, he also sired a missionary line, the “Guinnesses for God.” Arthur's grandson Henry Grattan Guinness became a famed evangelical orator (and, ironically, a teetotaler). He evangelized throughout Britain and wrote books on biblical prophecy. Henry’s daughter Geraldine married the son of Hudson Taylor, a famous missionary to China, and wrote Taylor’s biography. Modern apologist Os Guinness, carried out of China in a basket on a pole at the age of two by his missionary parents to escape the approaching Japanese army, is Henry’s great-grandson.

ONE WAY TO GET AWAY

NINETY MEMBERS of the communal society the Christian Brethren boarded the steamboat Megiddo in 1901 and set off to evangelize cities along the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. The members lived in family groups and supported themselves by making and selling crocheted goods, taking odd jobs in ports, collecting rent from properties the members owned in cities along the route, and charging the curious public admission for tours. After two years, navigational problems drove the group, now called the “Megiddo Mission,” onto land. In early 1904, they settled in Rochester, New York, where the Megiddo Church functions today.

AT WORK BEFORE DAYBREAK Children shuck oysters at the Pass Packing Company in Mississippi.

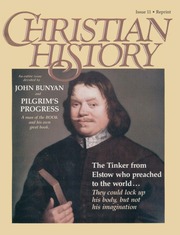

Christian History Magazine #11 - John Bunyan

With the cooperation of his jailer, Bunyan occasionally was permitted to leave his prison cell to go and preach to “unlawful assemblies” gathered in secret, after which he voluntarily returned to his jail cell.

Bunyan made shoelaces while imprisoned to support his family, “many hundred gross” by his own accounting.

In terms of numbers, Pilgrim’s Progress would have been a runaway best seller had it appeared in our day. 100,000 copies were in print in English alone in 1692!

In January 1672 the Bedford congregation called John Bunyan to be its pastor while he was still in prison.

While some Baptists proudly claim Bunyan, other Baptists today still disown him because of his tolerant position in his work Differences in Judgment About Water Baptism, No Bar to Communion.

When local magistrates sentenced Bunyan to imprisonment unless he promised them he would not preach, he refused, declaring that he would remain in prison till the moss grew on his eyelids rather than fail to do what God had commanded him to do.

In Bunyan’s day great preachers swayed public opinion as much as the mass media do today, which is one reason his unlicensed activities were perceived as a threat.

A stained-glass window is devoted to John Bunyan in Westminster Abbey, London.

Bunyan combined his skill as a tinker and his love of music to create an iron violin; later, during his imprisonment, he carved a flute from the leg of a stool that was part of his furniture.

When China’s Communist government printed Pilgrim’s Progress as an example of Western cultural heritage, an initial printing of 200,000 copies was sold out in three days!

Bunyan would have been released from prison if he would agree not to preach in “unlawful” or unlicensed assemblies. His own writings attest that he was given every opportunity to “conform.” It was a compromise he would not make.

The church Bunyan pastored still continues in the heart of Bedford, England. Now called “Bunyan Meeting,” it is affiliated with both the Baptists and Congregationalists.

Between the ages of 16 and 19, Bunyan served in the Parliamentary army.

The position for which Bunyan contended, and for which he went to jail, finally prevailed with the Act of Toleration of 1689, which recognized in England the religious rights of Dissenters and Non-conformists.

George Whitefield | Christian History Magazine

THOUGH LITTLE KNOWN TODAY, George Whitefield was America’s first celebrity. About 80 percent of all American colonists heard him preach at least once. Other than royalty, he was perhaps the only living person whose name would have been recognized by any colonial American.

America’s Great Awakening was sparked largely by Whitefield’s preaching tour of 1739–40. Though only 25 years old, the evangelist took America by storm. Whitefield’s farewell sermon on Boston Common drew 23,000 people—more than Boston’s entire population. It was probably the largest crowd that had ever gathered in America.

In his search for God before his conversion, Whitefield fasted to the point that he broke his health and, under doctor’s orders, was confined to bed for seven weeks.

Whitefield preached at both Harvard and New Haven College (Yale). At Harvard it was reported that “The College is entirely changed. The students are full of God.” Yet Harvard’s leading professors later wrote a pamphlet denouncing Whitefield.

Brutal mobs sometimes attacked Whitefield and his followers, maiming people and stripping women naked. Whitefield received three letters with death threats, and once he was stoned until nearly dead.

Whitefield usually awoke at 4 A.M. before beginning to preach at 5 or 6 A.M. In one week he often preached a dozen times or more and spent 40 or 50 hours in the pulpit.

George Whitefield married a woman he barely knew. Though he and his bride had corresponded, they had probably spent less than a week together before marrying. As many as four different ministers refused to marry the couple.

John Wesley is known as founder of the Methodist movement, but Whitefield formed a methodist society first. In fact, Whitefield pioneered most methods used in the 1700s’ evangelical awakenings: preaching in fields rather than churches, publishing a magazine, and holding conferences.

Whitefield pushed himself so hard and preached with such intensity that often afterward he had “a vast discharge from the stomach, usually with a considerable quantity of blood.”

Whitefield became close friends with Benjamin Franklin. Franklin once estimated that Whitefield, without any amplification, could be heard by more than 30,000 people.

George Whitefield traveled seven times to America, more than a dozen times to Scotland, and to Ireland, Bermuda, and Holland.

In his lifetime, Whitefield preached at least 18,000 times. He addressed perhaps 10,000,000 hearers.

When his 4-month-old son died, Whitefield did not stop preaching; he preached 3 times before the funeral and was preaching as the bells rang for the service itself.

Though Whitefield has been praised as “the greatest preacher that England has ever produced,” he spent little time formally preparing sermons. Whitefield’s secretary said, “I believe he knew nothing about such a kind of exercise.”

Whitefield was made the butt of several off- songs and a satirical play. Yet he was honored by famous poets Charles Wesley, William Cowper, and later, John Greenleaf Whittier, who described Whitefield as “That life of pure intent / That voice of warning yet eloquent, / Of one on the errands of angels sent.”

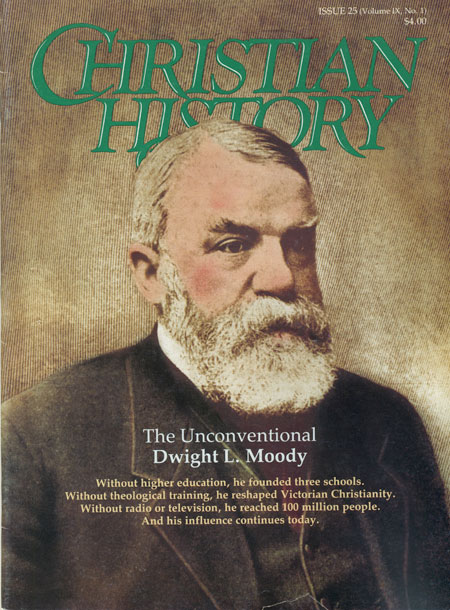

Issue 25 Unconventional Dwight L. Moody

The first time he applied for church membership, it was denied him because he failed an oral examination on Christian doctrine.

When he first came to Chicago in 1856, his goal in life was to amass a fortune of $100,000.

Moody ministered to soldiers in the American Civil War.

His engagement to Emma Revell was formalized by the unassuming announcement that he would no longer be free to escort other young ladies home after church meetings.

Abraham Lincoln visited Moody’s Sunday school, and President Grant attended one of his revival services.

He chose to use theaters and lecture halls rather than churches for his meetings.

Moody’s house in Chicago burned down twice; his Chicago YMCA building burned three times. Moody raised funds for the rebuilding each time.

D.L. Moody was never pastor of the church that grew out of his Sunday school work and that today bears his name.

At the Chicago World’s Exhibition in 1893, in a single day, over 130,000 people attended evangelistic meetings coordinated by Moody.

D.L. and his son Will survived a near-fatal accident at sea.

It is estimated that Moody traveled more than one million miles and addressed more than one hundred million people during his evangelistic career.

Moody’s revivals often elicited relief programs for the poor.

Moody once preached on Calvary’s hill on an Easter Sunday.

Moody was personally acquainted with George Muller, the orphanage founder; Lord Shaftesbury, the great social reformer; and Charles H. Spurgeon, the prince of preachers.

All three schools founded by Moody in the late nineteenth century are thriving today.

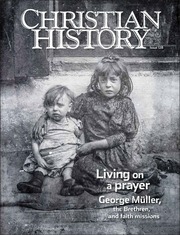

ENJOY THESE CLASSIC STORIES OF GEORGE MULLER AND HIS INFLUENCE FROM DELIGHTED IN GOD BY ROGER STEER

Take My money, please Müller decided to give up a set salary in 1830 and tell only the Lord about his needs. After he preached in Somerset, a congregant tried to give him money wrapped in paper, but Müller refused to accept it. The determined saint shoved the gift into Müller’s pocket and ran away.

Müller’s orphan home manifesto “The home will only be established,” Müller said in 1835, “if God provides the means and suitable staff to run it. . . . I don’t look to Bristol, nor even to England, but the living God, whose is the gold and the silver. . . . There will be no charge for admission and no restriction on entry on grounds of class or creed. All [staff] will have to be both true believers and appropriately qualified for the work. . . . Girls will be brought up for service, boys for trade. . . . The chief and special end . . . will be to seek, with God’s blessing, to bring the dear children to the knowledge of Jesus Christ by instructing them in the Scriptures.”

“Tried in spirit” One day in 1838, enough food was left for only one day— for 100 people. The staff, having given all they could, met as usual for prayer and went about their duties, but nothing came in. Müller returned to prayer; still nothing. How could he face the children tomorrow and announce no breakfast? He became “tried in spirit,” a rare occurrence. Then the bell rang. The woman at the door gave enough to provide for the next day’s needs.

A land miracle In 1846 Müller went to speak to the owner of the Ashley Down land. Finding him neither at work nor at home, Müller decided it wasn’t God’s will to meet that day. The next morning the gentleman said he had been kept awake all night until he made up his mind to let Müller have Ashley Down at £120 an acre instead of £200. “How good is the Lord!” thought Müller and signed an agreement to buy nearly seven acres.

From Müller to Moorhouse to Moody In 1856 young Irishman James McQuilkin read part of Müller’s Narratives. “See what Mr. Müller obtains simply by prayer,” he thought. With some friends he organized meetings near Ballymena; hundreds prayed and repented in the streets. Revival spread to hundreds of thousands—including Henry Moorhouse who converted from gambling and drinking and met D. L. Moody in Dublin. Later Moody heard Moorhouse preach about God’s love in Chicago, saying afterward, “I have preached a different gospel since, and I have had more power with God and man since then.”

A milk and bread miracle One of the best-loved Müller stories comes to us from Abigail Townsend Luffe. When she was a child, her father assisted Müller, and she spent time at Ashley Down. Early one morning Müller led her into the long dining room set for breakfast but without food, praying, “Dear Father, we thank Thee for what Thou art going to give us to eat.” There was a knock at the door; it was the baker, unable to sleep because he was sure the Lord wanted him to bake bread for Müller. “Children,” Müller said, ”we not only have bread, but fresh bread.” Almost immediately they heard a second knock. It was the milkman; the milk cart had broken down outside the orphanage, and he offered the milk to the children, completing their meal.

Müller’s secret “There was a day when I died, utterly died,” Müller once said, “to George Müller, his opinions, preferences, tastes, and will—died to the world, its approval or censure—died to the approval or blame of even my brethren and friends—and since then I have studied to show myself approved only unto God.” C H

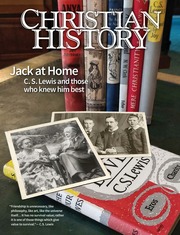

Christian History Magazine #140 - Jack at home: C. S. Lewis and those who knew him best (See also Issue 7 - C S Lewis)

NO PRUNES FOR ME In his essay “On Three Ways of Writing for Children,” Lewis recalled announcing “I loathe prunes” very loudly in the dining room of a hotel. A little boy nearby announced just as loudly, “So do L” Lewis evidenced similar empathy in writing to children—speaking about their daily lives, critiquing the writings they sent him, and discussing God. In a letter written the day before he died, he noted to one boy, “All the children who have written to me see at once who Aslan is, and grownups never do!”

THE BLUE COW ON THE PIANO Eric Routley (1917-1982), later a famous church musician and composer, was an undergraduate at Oxford during World War II and attended a Socratic Club meeting Lewis was chairing. There, Routley said, “students crowded into a room and sat on the floor or under the piano.” When one of the students asked during the discussion how one could prove anything, including whether there was a blue cow on the piano, Lewis responded, “Well, in what sense blue?”

THE ORIGINAL MEDIA FAST Derek Brewer (1923-2008), a Chaucer scholar, studied under Lewis in the mid-1940s. Lewis once told Brewer he “lack[ed] pep,” but supported his later scholarship, serving as general editor for one of Brewer’s Chaucer editions. Brewer recalled that Lewis never read newspapers because, Lewis said, “Someone will always tell you if anything has happened.”

WHEN THE BOMBS FELL Many of Lewis’s writings responded directly or indirectly to horrors of war

“STEINER SAYS” Daphne Olivier Harwood (1889-1950), first wife of Lewis’s friend Cecil Harwood (18981975), was actor Laurence Olivier’s (1907-1989) cousin. An Anthroposophist, she introduced both Harwood and Lewis’s friend Owen Barfield to this complex mystical philosophy founded by Rudoph Steiner (1861-1925).

Lewis once exclaimed in reaction to her criticism that he was making Christianity too authoritarian, “When you have heard half as many sentences beginning ‘Christianity teaches’ from me as I have heard ones beginning ‘Steiner says’ from you & Cecil & Owen & [another friend]—why then we'll start talking about authoritarianism!” But he greatly admired them both, describing Harwood as “the sole Horatio known to me in this age of Hamlets.”....

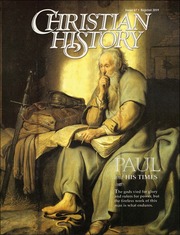

Christian History Magazine #47 - Paul and His Times

Little-known and remarkable facts about Paul and his times. by MARVIN R. WILSON

Tarsus, Paul’s birthplace, is at least 4,000 years old. In 41 B.C., Antony and Cleopatra held a celebrated meeting there.

At least seven of Paul’s relatives are mentioned in the New Testament. At the end of his letter to the Romans, Paul greets as “relatives” Andronicus and Junia, Jason, Sosipater, and Lucius. In addition, Acts mentions Paul’s sister and his nephew, who helped Paul in prison (Acts 23:16–22).

It is possible that Paul’s “relative” Lucius is Luke, the author of the Gospel and the Acts of the Apostles. On his second missionary journey, Paul may have gone to Troas (where Luke lived—or at least where he joined Paul) because he knew a relative he could stay with there (Acts 16:8, 11).

What type of fish did Paul eat? Probably not catfish. Catfish was the largest native fish of the Sea of Galilee (sometimes weighing up to 20 pounds), but Jewish dietary laws would have prevented at least the early Paul from eating fish without scales (Deut. 14:10).

It’s not clear exactly how Paul supported himself on his missionary journeys. Luke calls him a “tent-maker” (skenopoios), which suggests Paul was a weaver of tent cloth from goats’ hair. The term, however, can also mean “leatherworker.” Other early translations of Luke’s term mean “maker of leather thongs” and “shoemaker.”

Paul, the “Apostle to the Gentiles,” had plenty of opportunity to preach to Jews in his travels. There were some four to five million Jews living abroad in the first century. Every major city had at least one synagogue, and Rome had at least eleven. The Jewish population of Rome alone was 40,000–50,000.

Wine was a common drink of Paul’s day, but it was not the wine of our day. In the Greco-Roman world, pure wine was considered strong and unpleasant, so some Greeks diluted wine with seawater. In cold weather, city snack shops in Italy sold hot wine.

Paul read pagan poets. In his writings, he quotes Epimenides of Crete (Tit. 1:12), Aratus of Cilicia (Acts 17:28) and Menander, author of the Greek comedy Thais (1 Cor. 15:33).

Many Roman men of Paul’s day curled their hair. Men also applied oil and grease to their hair; it was one way people de-loused themselves. These concoctions were made from such substances as the marrow of deer bones, the fat of bears and sheep, and the excrement of rats.

Demand for wild animals for entertainment in Paul’s day turned hunting into a major business. Gladiatorial shows usually included animal hunts or fights with leopards, panthers, bears, lions, tigers, elephants, ostriches, and gazelles. In 55 B.C. at Pompeii’s games, 400 leopards and 600 lions were killed. In A.D. 80, at the dedication of the Colosseum by Emperor Titus, 9,000 animals were killed in a hundred days.

Paul may have recorded some of the New Testament church’s hymns. Many scholars think Paul is quoting hymns in passages like 1 Corinthians 13 and Philippians 2:1–11.

Paul’s letters, not the Gospels, give us the earliest information we have about Jesus. All his letters were probably written before the first Gospel was penned. The earliest reference to the sayings of Jesus come from 1 Thessalonians, which Paul wrote about A.D. 50.

He may have not been as old as the Rembrandt painting on cover implies, but Paul lived a relatively long life. He was probably born about A.D. 6 and probably died about A.D. 64—which means he may have died at about age 58, an old age given the times and the hard life he lived.

In later art, Paul is often depicted with a sword and book, which is said to symbolize the manner of his death (beheading by sword), and his writings, which became “the sword of the Spirit.”

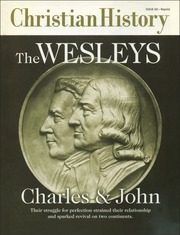

Christian History Magazine #69 - Wesleys: Charles and John

Interesting and unusual facts about John and Charles Wesley.

Christmas Miracle When Charles was born, on December 18, 1707, his parents thought he was dead because he neither cried nor opened his eyes. He was several weeks premature, so they wrapped him in wool until the day he should have been delivered. He eventually came around and apparently had a healthy childhood. His parents lost eight or nine other children in infancy.Books Are Made for Walking The Wesley brothers never hitched a ride from college—they walked the 150 miles to Epworth instead. The journey was often marred by bad roads, inclement weather, and even highwaymen. To make matters worse, the brothers read books while they walked. The trip scared their father so badly that he once told them, “I should be so pleased to see ye here this spring, if it was not upon the hard conditions of your walking hither.” John maintained that reading for 10 of his 25 daily miles never caused any harm.

Prickly Peer The curmudgeonly Samuel Johnson (1709–1784) had mixed feelings about the Wesleys. He knew John at Oxford, and said of him, “John Wesley’s conversation is good, but he is never at leisure. He is always obliged to go at a certain hour. This is very disagreeable to a man who loves to fold his legs and have out his talk, as I do.” Johnson later applauded Oxford’s expulsion of six Methodist students (see page 22), which could hardly have endeared him to the movement’s founding family. Yet at the end of his life, he wanted to invite John’s brilliant but financially restricted sister Martha to live at his house. Unfortunately, Johnson died before his wish could be carried out.

“An Odd Way of Thinking” Susanna Wesley was not quite sure what to make of her sons’ heart-warming conversion experiences. She wrote to Charles, “I think you are fallen into an odd way of thinking. You say that till within a few months you had no spiritual life, nor any justifying faith. Now this is as if a man should affirm he was not alive in his infancy, because when an infant he did not know he was alive. All, then, that I can gather from your letter is that till a little while ago you were not so well satisfied of your being a Christian as you are now.”

Pepper-upper Charles could sympathize with today’s caffeine addicts. In 1746 he tried to give up tea, but writes, “my flesh protested against it. I was but half awake and half alive all day; and my headache so increased toward noon, that I could neither speak nor think.… This so weakened me, that I could hardly sit my horse.”

Thanks, but No Thanks Though the Methodists earned early acclaim for their ministry to marginalized groups such as prisoners, orphans, and the ill, they later became so unpopular that even these doors closed to them. As John recorded in his journal for February 22, 1750, “So we are forbid to go to Newgate [a prison], for fear of making them wicked; and to Bedlam [an asylum], for fear of driving them mad!”

Not Dead Yet In 1753, John became so ill that his doctor thought he would die. Just in case, John penned this epitaph:

Here lieth the Body

of

John Wesley

A brand plucked out of the burning:

who died of a consumption in the fifty-first year of his age,

not leaving,

after his debts are paid,

ten pounds behind him:

praying,

God be merciful to me, an unprofitable servant!John, whose mother had called him “a brand plucked out of the burning” after he was rescued from a house fire in 1709, resolved to cheat death again. Two days after he wrote the epitaph, he made himself a poultice of brimstone (sulfur), egg white, and brown paper, which immediately relieved his pain. He recovered and lived another 38 years.

Ready to Rumble After increasingly severe earthquakes in England on February 8 and March 8, 1750, a self-proclaimed prophet predicted another quake in April that would destroy half of London. The city went berserk. Charles wrote 19 hymns on the subject and published a sermon called “The Cause and Cure of Earthquakes.” On the foretold night, John reported, “Places of worship were packed, especially the chapels of the Methodists.” Nothing happened.

See also John and Charles Wesley | Christian History

See also John Wesley - Revival and Revolution

The History of Worship from Constantine to the Reformation takes readers on a one thousand year journey into the fascinating history of worship practices.

David Livingstone, Missionary Explorer:

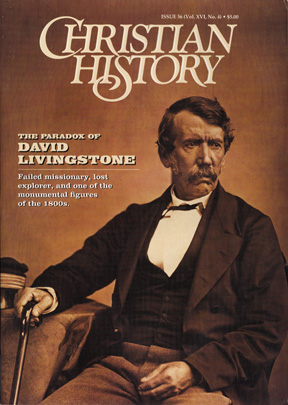

The Paradox of David Livingstone: Did You Know? Little-known or remarkable facts about David Livingstone: missionary explorer by by Ruth A. Tucker

Though Livingstone is remembered as a missionary, only one-third of his 30 years in Africa were spent in the service of a mission board. Even during that time, he went his own way, often ignoring the advice and directives of colleagues and superiors.

Livingstone started life as did millions of other children in the industrial revolution: exploited by a society bereft of child labor laws. At age 10, he worked 14-hour days in a cotton factory, followed by two hours of night school. He grew up in a one-room tenement that overlooked the cotton mill where he worked.

With his first week's wages, Livingstone purchased a copy of Ruddiman's Rudiments of Latin. To break the tedium in the factory, he propped the book on the frame of his machine and studied while he worked. Livingstone was determined to become a missionary to China but was prevented from doing so by the outbreak of the Opium War.

Livingstone closely connected mission work with social and economic progress. The only way to fight the slave trade in Africa, he said, was through "Christianity, Commerce, and Civilization."

From his earliest years in Africa, Livingstone was often critical of fellow missionaries. Soon after he arrived in the Cape Colony, he wrote, "The missionaries in the interior are, I am grieved to say, a sorry set. … I shall be glad when I get away into the region beyond—away from their envy and backbiting." He added that there was no more affection between them and himself than there was between his "riding ox and his grandmother."

Livingstone's penchant for exploring could not help but affect his family life. He and his wife, Mary, lived in the same house together only four of the seventeen years of their marriage. When Mary Moffat, Livingstone's mother-in-law, heard that he had taken her daughter and grandchildren on another dangerous exploring expedition, she wrote him a stinging letter, signed, "I remain yours in great perturbation. M. Moffat."

Unlike his fellow explorers and traveling companions, Livingstone enjoyed relatively good health during his first years in Africa. He traversed the continent for a dozen years before he fell ill with "African fever." At that time, he experimented with the local witch doctors to test their healing powers but concluded, after being "smoked like a red-herring over green twigs" and put under their charms, that European medical practices were superior.

Livingstone was the first European to feast his eyes on the great Victoria Falls: "Five columns of smoke [i.e., mist] arose. … The whole scene was extremely beautiful; the banks and islands dotted over the river are adorned with sylvan vegetation of great variety and form … scenes so lovely must have been gazed upon by angels in their flight."

During his first visit back to the British Isles (1856-1858), Livingstone became a national hero. He was awarded a gold medal from the Royal Geographical Society, an honorary doctorate from Oxford University, and a private audience with Queen Victoria. He was mobbed in the streets; when he attended church, chaos ensued as people climbed over pews to shake his hand.

Livingstone is considered one of history's greatest explorers, but his last two expeditions failed in their chief aims: The Zambezi Expedition sought to discover a navigable river that cut across southern Africa, and in his final adventure, Livingstone sought to find the source of the Nile.

Though Livingstone did little traditional missionary work while he was alive, after his death, he inspired hundreds of men and women to give their lives for African missions. Mary Slessor, for example, decided to follow in the footsteps of her hero and, in 1875, arrived in Calabar (in present-day Nigeria). She quickly became a living legend as an explorer and evangelist—and vice counsel for the British Empire. Peter Cameron Scott, founder of the Africa Inland Mission, was inspired to return to Africa after his first mission failed when he read the inscription on Livingstone's tomb in Westminster Abbey: "Other sheep I have which are not of this fold; them also I must bring."

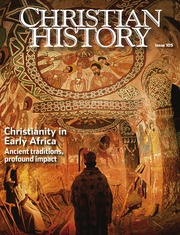

Christianity In Early Africa See Index

India: A Faith of Many Colors (Christian History Magazine Issue 87)

Interesting facts about Christianity in India

What No Storm Can Wash Away The tsunami that wreaked so much destruction across the Indian Ocean on Sunday morning, December 26, 2004, devastated towns along India’s shore that boast significant Christian populations. In the picture at left, a Catholic shrine (called the “Lourdes of the East” as it attracts millions of pilgrims each year) overlooks overturned storefronts in the town of Vailankanni. Vailankanni is located on the shores of the southeastern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, which is a bastion of both Catholic and Protestant Christianity. Catholic missionaries planted churches there in the 16th century and Pietists in the 18th. Tamil Nadu is the supposed burial place of the Apostle Thomas and is associated with a number of famous Christian leaders including the Irish missionary Amy Carmichael, the historian Stephen Neill, the theologian Lesslie Newbigin, and the popular apologist Ravi Zacharias.India’s Apostle Indian Christians claim an ancient heritage. According to tradition, the Apostle Thomas landed on the Malabar coast of southwest India in A.D. 52. He healed the sick and demon-possessed, converted people from various castes, and finally died in Mylapore (now within the huge city of Madras, recently renamed Chennai) at the hands of hostile Brahmans. The second-century Acts of Thomas relates that Thomas encountered an Indian official named Abban in Jerusalem, who invited him to come to India to build a palace for King Gundaphorus. Thomas agreed to go with Abban, and the king eventually became a believer.

Indian Christians still make pilgrimages to shrines that remember Thomas. As an act of penance on Good Friday, Catholic nuns carry wooden crosses nearly 2,000 feet up a hill in Malayatoor, Kerala, where Thomas is believed to have spent many days in prayer. The traditional burial site atop St. Thomas Mount in Madras has been venerated for at least 1500 years.

Palm-leaf, copperplate, and stone inscriptions all attest to a living church in India dating to the first few centuries of the Christian era. Today, at least six communities in India still claim the link to Thomas—the Orthodox Syrian Church, the Independent Syrian Church of Malabar, the Mar Thoma Church, the Malankara Catholic Church, the Church of the East, and the St. Thomas Evangelical Church.The Most Christian Part of India Given that many of our articles focus on southern India, this issue could give the impression that Christianity thrives only in the south. But that’s not true—American Baptist and Welsh Presbyterian missionaries brought Christianity to northeast India in the late 19th century, and today Christians actually have a proportionately stronger presence in some of India’s northeastern states than they do in the south. According to the 1991 Indian census, nearly 90 percent of the people of Nagaland, a tiny state on the border with Myanmar, claim to be Christian—making it the most Christianized region in all of Asia second only to the Philippines. Other tribes like the Khasis and Garos in the state of Meghalaya (once part of Assam) or the Mizos in Mizoram likewise embraced Christianity—over 85 percent of Mizos today are Christians, as are 65 percent of the people in Meghalaya. All of these people are adivasis, aboriginal hill people who have never been part of the Hindu mainstream.

An Influential Minority Christianity’s impact on the Indian subcontinent has been deeper and more widespread than its minority status would suggest. Although Christians officially comprise only 2.4 percent of the Indian population (census figures that are likely underestimated), Christian schools, colleges, hospitals and printing presses have extended Christianity’s impact into vast areas of resiliently non-Christian Hindu and Muslim society. Today, Christian colleges consistently rank among the nation’s best, having educated many generations of India’s non-Christian, as well as Christian, elites. Even Mohandas K. Gandhi, who was inspired by the life of Jesus Christ, was educated at a mission school—although he opposed Christian missionaries to the end of his life.

A Religious Philosophy with “Dark Cellars” Swami Vivekananda became famous in the West for his speech to the Parliament of Religions held in Chicago in 1893. There he praised the noble and rich spiritual heritage of India and persuaded his audience to recognize and elevate “Hinduism” into the rank of a “world religion.” His mission to plant exotic notions of an exalted “Hindu” spirituality in the minds of Westerners remains active today in countless Vedanta Societies. Vivekananda came to America in order to “correct” the impression given by his contemporary Pandita Ramabai, a well-known Christian convert and reformer who had been sending a very different message. Ramabai contrasted Vivekananda’s “poetry” of sentiment with her “prose” of harsh reality. She wrote, “I beg my western sisters not to be satisfied with looking at the outside beauty of the grand philosophies, and not to be charmed with hearing the interesting discourses about educated men, but to open the trap doors of the great monuments of ancient Hindoo [sic] intellect and enter into the dark cellars where they will see the real workings of these philosophies.” Ramabai, who passionately ministered to India’s destitute women and children, knew only too well how ugly Hindu life could look in practice. She had lived in its strongholds, and she observed Hindu priests “oppress the widows” and “trample the poor, ignorant, low-caste people under their heels.”

Missionary with Style No one better represents the high tradition of Christian scholarship in India than the Italian Jesuit Constanzo Guiseppe Beschi (1680–1747). His long list of writings—epic poems written in the classical style, philosophical treatises, commentaries, dictionaries, grammars, translations, and polemical tracts—put him at the very forefront of Tamil scholars. His lavish lifestyle also made quite an impression. Traveling in state, he wore a long tunic bordered in scarlet, covered by a robe of pale purple, with ornate sandals or slippers, white and purple turban, pearl and ruby earrings, rings of heavy gold, and a long carved and decorously inlaid staff. He was carried in a sumptuous palanquin that had a tiger’s skin for him to sit upon, two attendants to fan him, someone holding a purple silk parasol surmounted by a golden ball to shield him from the sun, and a spread tail of peacock feathers going before him. In short, Beschi’s circuits assumed all pomp and pageantry with which Hindu gurus usually traveled.

Modeling Unity for the Church India has had an important impact on Christianity worldwide. Frustrated by the doubly divisive impact of caste and denomination on the church’s witness to Hindu-Muslim culture, Indian Christians joined with missionaries to create the Church of South India (CSI) in 1947 and the Church of North India (CNI) in 1948. This was the first unification of Episcopal and non-Episcopal Protestant churches since the Reformation and provided an important model for the emerging ecumenical movement in the West. Still, the majority of non-Catholic and non-Thomas Christians in India do not belong to either of these groups. Today, the largest and most rapidly growing Christian movement in India is Pentecostalism. Contributed by Steven Gertz, Robert Eric Frykenberg, Susan Billington Harper, and Keith J. White.

Christian History Magazine #101: Healthcare and Hospitals

IN THE EARLY YEARS of the faith, pagans and Christians shared similar attitudes toward medicine and healing, but the church fathers believed God created the material world for the use of humankind, and this influenced their views of medicine:

Clement held that, within God’s created order, understanding is from God, and many things in life arise from the exercise of human reason, although its kindling spark comes from God. Health obtained through medicine is one of these things that has its origin and existence as a consequence of divine Providence as well as human cooperation.…

Origen, in a homily on Numbers, quotes Ecclesiasticus 19:19—“All wisdom is from God”—and a little later asks, if all knowledge is from God, what knowledge could have a greater claim to such an origin than medicine, the knowledge of health? Just as God causes herbs to grow, so also did he give medical knowledge to men. God did this in his kindness, knowing the frailty of our bodies and not wishing for us to be without succor when illness strikes. Thus Origen can call medicine “beneficial and essential to mankind.”

Basil also regarded all the arts as God’s gift, given to remedy nature’s deficiencies. Accordingly, the medical art was given to relieve the sick, “in some degree at least.” Gregory of Nyssa records that, when his sister was ill, their mother had begged her to let a physician treat her, arguing that God gave the art of medicine to men for their preservation. John Chrysostom also writes that God gave us physicians and medicine, and Augustine attributes the healing properties of medicine to God. (Source: Darrel Amundsen, Medicine, Society, and Faith in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds.)

DON YOUR “SICK SUIT” By the Middle Ages, long-term residents of hospitals received clothes, in many cases a uniform with a distinctive badge. Black, white, dark brown, blue, and gray were popular uniform colors. Badges might consist of crosses or of an image related to the patron saint of the hospital or to the name or heraldic device of its founder. Distinct styles of uniform might also be worn by staff to distinguish them from patients. Finally, uniforms could prove helpful in keeping tabs on hospital residents in cases where they were allowed to leave the hospital (if, for example, they were not violently ill, or if they were poor or elderly but not infirm).

IT’S BEDLAM IN HERE! The priory of St. Mary of Bethlehem in London was founded in 1247 and specialized in mental illness. Its name in colloquial speech was pronounced “Bedlam,” and it became notorious in later years for its substandard treatment of patients (which included allowing the public in to look at them for a small admission fee). Its notoriety eventually gave a general word for “chaos” and “uproar” to the English language.

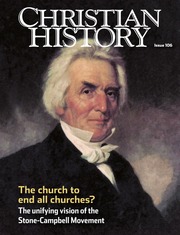

Christian History Magazine #106 - Stone-Campbell Movement

FROM LBJ TO ZIMBABWE SEVERAL PRESIDENTS have been members of the Stone-Campbell tradition. The first was James Garfield. Baptized at age 18, Garfield began preaching at age 21 and is the only U.S. president who was a minister (of a Christian Church in Cleveland, Ohio). He was also among the group that launched the magazine Christian Standard, still published today. The second was Lyndon Baines Johnson. As a young man, he was baptized in a small Christian Church in Johnson City, Texas, where he also attended services in his retirement. Church was also a focal point of Ronald Reagan’s youth in Dixon, Illinois. He was a member of First Christian Church and graduated from Disciples-affiliated Eureka College in 1932. While there, one of his first stage roles was as a Christian Church minister. Politician Sir Garfield Todd (see “Worldwide disciples, worldwide Christians,” pp. 34–36) was a minister at a New Zealand Church of Christ before moving to Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) in 1934. For a decade, he wore the hats of missionary, schoolteacher, bricklayer, and occasional doctor. He entered politics in 1942 and by 1953 was prime minister of Southern Rhodesia, where he worked for equal rights for all Africans. Queen Elizabeth II knighted Todd in 1986, but in 2002 he was stripped of Zimbabwean citizenship.

TOP MAN AT YALE; HOOPS HERO He visits Civil War battlefields for fun and at his day job explains how early Jews and Christians adapted to the culture around them without adopting its values. He is Greg Sterling, appointed dean of Yale Divinity School in 2012—a noted New Testament scholar, former dean at Notre Dame, and minister in Churches of Christ. Sterling’s appointment at Yale testifies to the passion for biblical scholarship that has always characterized the Stone-Campbell tradition (see “Reading the Bible to enjoy the God of the Bible,” p. 16). In 1963 Disciples’s magazine World Call featured basketball phenomenon John Wooden. He later won 10 NCAA Championships, appeared 16 times in the Final Four, had 40 strong seasons, and was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame twice—as a student and as a coach. A deacon at and generous donor to First Christian Church of Santa Monica, California, Wooden was present every Sunday except when his team was on the road.

SONGS BY THE DEAD Janis Joplin grew up in Port Arthur, Texas, a “rough” refinery town near Houston. Before she burst onto the national music scene in 1967, she taught Sunday school and sang in the youth choir at First Christian Church. The church’s historian noted on Joplin’s baptism card: “Died of a drug overdose in a Beverly Hills hotel.… She was cremated and her ashes were strewn along the coastline of Northern California. She had also set aside $2,500 for [her] wake. The Grateful Dead and others provided music for the wake.”

STARDUST AND COUNTRY MUSIC Though Hoagland (Hoagy) Carmichael failed at practicing law, he had music to fall back on—inspired by his mother, who played for dances and accompanied silent movies. He wrote “Stardust” (one of the most recorded songs ever), “Old Buttermilk Sky,” and “Georgia on My Mind.” An active member at North Hollywood Christian Church in California, he performed for the 1962 convention of the Disciples of Christ. And, does singing unaccompanied in church spark a musical career? Pop and country singers Pat Boone, Glen Campbell, Roy Orbison, and Loretta Lynn were all raised in or converted to Churches of Christ.

WOMAN WITH THE HATCHET Carry Nation was born in Kentucky and baptized in a stream in Missouri with ice floating in the water. She began her temperance crusade after the death of her first husband from alcoholism and earned the nickname “The Home Defender” as a result of taking her hatchet to whiskey bottles and saloon furnishings.

Her second husband, David Nation, divorced her in 1901, citing abandonment. In 1902, calling her a “stumbling block and a disturber of the peace,” her Disciples church disfellowshipped her. But frightened of their decision, they provided her a letter of commendation so she could transfer her membership elsewhere.

Other famous, or infamous, people connected with the tradition included golfer Ben Hogan, bank robber John Dillinger, Lew Wallace (author of Ben-Hur), and James Warren Jones, pastor at Jonestown, Guyana.

How the Church in China Survived and Thrived in the 20th Century (Christian History #98

On the eve of the Communist victory in 1949, there were around one million Protestants (of all denominations) in China. In 2007, even the most conservative official polls reported 40 million, and these do not take into account the millions of secret Christians in the Communist Party and the government. What accounts for this astounding growth? Many observers point to the role of Chinese house churches.

The house-church movement began in the pre-1949 missionary era. New converts—especially in evangelical missions like the China Inland Mission and the Christian & Missionary Alliance—would often meet in homes. Also, the rapidly growing independent churches, such as the True Jesus Church, the Little Flock, and the Jesus Family, stressed lay ministry and evangelism. The Little Flock had no pastors, relying on every “brother” to lead ministry, and attracted many educated city people and students who were dissatisfied with the traditional foreign missions and denominations. The Jesus Family practiced communal living and attracted the rural poor. These independent churches were uniquely placed to survive, and eventually flourish, in the new, strictly-controlled environment.

In the early 1950s, the Three-Self Patriotic Movement eliminated denominations and created a stifling political control over the dwindling churches. Many believers quietly began to pull out of this system. They chose to meet in homes, although such activity was highly dangerous. According to a Communist source, by the mid-1950s these groups had grown to be “more numerous than all the other Protestant churches combined.”

In 1953, the chairman of the Communist-controlled Religious Affairs Bureau attacked the “rapid growth of meetings in the home” as “suspicious.” By 1958, the year of enforced “church unity,” the TSPM was prohibiting house churches altogether: “All so-called ‘churches’, ‘worship-halls’ and ‘family-meetings’ which have been established without the permission of the government must be dissolved.”

At “accusation meetings,” Christians were encouraged to denounce their own leaders as “lackeys of Western imperialism.” Despite this, a number of key evangelical leaders took a stand against Communist Party interference in church affairs. Wang Mingdao, pastor of the independent Christian Tabernacle in Beijing, accused Y. T. Wu (the first chairman of the TSPM) and his later successor Bishop K. H. Ting of denying the basic doctrines of evangelical faith. Wang was imprisoned for 23 years. In the south, Baptist-trained Lin Xiangao (later known as Pastor Lamb) was also imprisoned and sent to do slave labor in the coal mines. Allen Yuan in Beijing was sent to labor camp for opposing the TSPM. Many others were also persecuted. It is very doubtful whether the church would have survived in China without their sterling testimony and patient, Christ-like suffering in the dark days under Mao.

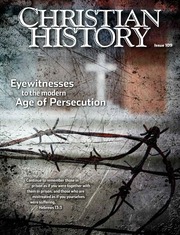

Christian History Magazine #109: Persecution

CHRISTIANS HAVE SUFFERED FOR THEIR FAITH THROUGHOUT HISTORY. HERE ARE SOME OF THEIR STORIES*

SERVING CHRIST UNTIL THE END Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna, is one of the earliest martyrs about whom we have an eyewitness account. In the second century, his church in Smyrna fell under great persecution. When soldiers came to arrest him, Polycarp ordered food set before them and asked for an hour to pray. His prayer was so impressive that the soldiers questioned their orders. They allowed him not one but two hours before leading him back to town. There a magistrate ordered Polycarp to renounce Christ and give obedience to Caesar as Lord. Polycarp answered: “Eighty and six years have I served Christ, nor has He ever done me any harm. How, then, could I blaspheme my King who saved me?” In February 155 he died at the stake.ANOTHER WILL SUFFER FOR ME Felicitas, a Christian slave arrested with her friends in the Roman persecution of 202 for refusing to sacrifice to pagan gods, was a catechumen preparing for baptism and in her eighth month of pregnancy. She feared her condition would require her to die alone for her faith later, because Roman law did not permit execution of pregnant women. But soon she went into early labor. As she groaned in pain, servants asked how she would endure martyrdom if she could hardly bear the pain of childbirth. She answered, “Now it is I who suffer. Then there will be another in me, who will suffer for me, because I am also about to suffer for him.” An unnamed Christian woman took in her newborn daughter. Felicitas and her companions were martyred together in the arena in March 202.

IMPRISONED FOR ORTHODOXY In 524 scholar and politician Boethius lay on his bed, overwhelmed by gloom. Born to wealth, he slept on dirty straw. Once a consul in Rome, he was now the toy of cruel soldiers. The greatest mind of the age was in jail. Why? An orthodox Christian, he defended the doctrine of the Trinity, whereas his ruler, Theodoric the Ostrogoth, was an Arian. Boethius had stood against many corrupt office-holders in his career. They now slandered him to Theodoric, who jailed and tortured him. A frightened senate declared Boethius guilty. He was eventually killed in October 524. But on death row, Boethius imagined Philosophy entering his cell as a splendidly dressed lady, seating herself at the end of his bed and addressing him. Soon he was at work in his cell writing his greatest book, The Consolation of Philosophy, beloved for centuries.

“GOD WILL NOT LET ME DOWN” Thomas von Imbroek was a sixteenth-century printer at Cologne on the Rhine, an Anabaptist, and a man of peaceable, Christian spirit. His failure to baptize his children brought him to the attention of authorities in 1557. Months passed in which he was tortured and pressured to convert to Catholicism. To his persecutors he offered this speech: “I am willing and ready, both to live or to die. I do not care what happens to me. God will not let me down.… Sword, water, fire … cannot frighten me.… All the persecution in this world shall not be able to separate me from God.” He was beheaded in March 1558.

THE LADDER TO HEAVEN Gorcum in the Netherlands, a town torn by war between Catholic Spaniards and Protestant Dutch, was seized by Dutch sailors known as the “Sea Beggars” in June 1572. They assaulted a citadel in which Catholic believers had holed up. Eventually they freed the laypeople, but subjected the priests to mock executions and ridicule, trying to get them to renounce the faith.

Father Nicolas Pik’s release was obtained by his brothers. But he refused to abandon his fellow captives, saying that if he did so he would fall into hell. “Let me rather go to heaven at once. Death does not frighten me,” he said. When the captives were hung, Pik offered himself to the noose first, saying, “I show you the ladder to heaven. Follow me like valiant soldiers of Jesus Christ.”TROUBLED BY SAFETY In August 1643 missionary to Canada Isaac Jogues watched from a hiding place as Iroquois Indians captured fellow missionaries and Huron allies. Troubled by his safety, he realized he could not abandon them “without giving them the help which the Church of my God has entrusted to me.” He stepped forward and gave himself up. In captivity Jogues won the respect of the Iroquois. When freed he returned to France but was embarrassed by the praise lavished on him. Eventually he returned to Canada, where he was tomahawked during a negotiation turned violent. Before the Indian who killed Jogues was hung, he converted to Christianity and took “Isaac Jogues” as his baptismal name.

GRACE TO LOVE HIS ENEMIES Idi Amin seized power as Uganda’s president in 1971 and butchered 300,000 Christians. In January 1977 Anglican bishop Festo Kivengere challenged the killings in a sermon. Threatened with death, Kivengere fled with his family to neighboring Kenya, where he wrote the book I Love Idi Amin. “The Holy Spirit showed me,” he wrote, “that I was getting hard in my spirit, and that my hardness and bitterness toward those who were persecuting us could only bring spiritual loss.… So I had to ask for forgiveness from the Lord, and for grace to love President Amin more.” When he could safely return to Uganda, he preached love, forgiveness, and reconciliation to the bruised nation.

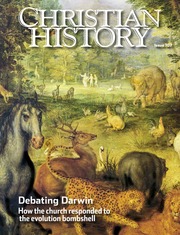

Christian History Magazine #107: Charles Darwin - See Index

Issue #107 of the Christian History magazine examines the responses of 19th century Christians to the challenge of Darwinian evolution. Read about the reactions of theologians, scientists, pastors, authors, bishops, and politicians as they grapple with the questions of Darwinism in many and diverse ways—ranging from hostility to reconciliation—and learn how Darwinism eventually became a symbol of warfare between science and Christianity.

DARWIN ALMOST MISSED THE BOAT Among the careers Darwin considered before making his fateful Beagle voyage was medicine (his father’s choice). But his attempt to become a doctor was foiled by his inability to stand the sight of blood. When the voyage was proposed, he was not the first choice, and when he was offered a position, his father turned it down on his behalf. When Darwin finally did make it onto the boat, he was seasick for most of the voyage— one of the reasons he spent so much time off the boat collecting specimens on solid ground.

FAVORED RACES The full title of Darwin’s book was On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. Darwin did not argue there that humans descended from nonhuman ancestors. That book came a little over a decade later, in 1871: The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex. Much of the controversy over Darwin’s theories followed this later book. During Darwin's own lifetime, neither sold as well as his last book—on earthworms.

LIVING IN A MATERIAL WORLD In 1984 pop star Madonna crooned about being a material girl in a material world, but was she aware of the intellectual roots of the word? Philosophically “materialism” means that “matter” is the only thing in the universe— that thoughts, feelings, and even the soul are ultimately reducible to aspects of physical reality. This was an intellectual trend in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and some Christians thought Darwin fit right in—that his theory was “godless materialism” that explained existence without any reference to spiritual realities.

DIFFERENT STROKES Scientists responded differently to Darwin in different places. There were many questions in New Zealand about whether its original inhabitants should have land rights, or whether they had been proven “unfit” in the struggle with white settlers. So scientists there seized on struggle as the fundamental principle in Darwin's theory. But half a world away, most Russian naturalists conducted their field work in Siberia, where populations were not dense and cooperation was crucial for a group’s survival. Their version of Darwin's theory replaced the struggle element with cooperation.

DARWIN DEBATES HIMSELF In a note jotted down while single, Darwin cited as reasons for marrying: “Children—(if it Please God)—Constant companion, (& friend in old age) who will feel interested in one,—object to be beloved & played with.—better than a dog anyhow.—Home, & someone to take care of house—Charms of music & female chit-chat.—These things good for one’s health.—Forced to visit & receive relations but terrible loss of time.”

Reasons for not marrying included “Freedom to go where one liked—choice of Society & little of it.—Conversation of clever men at clubs—Not forced to visit relatives, & to bend in every trifle.—to have the expense & anxiety of children—perhaps quarrelling—Loss of time.—cannot read in the Evenings—fatness & idleness—Anxiety & responsibility—less money for books &c—if many children forced to gain one’s bread.—(But then it is very bad for ones health to work too much).”